From Texas Public Radio:

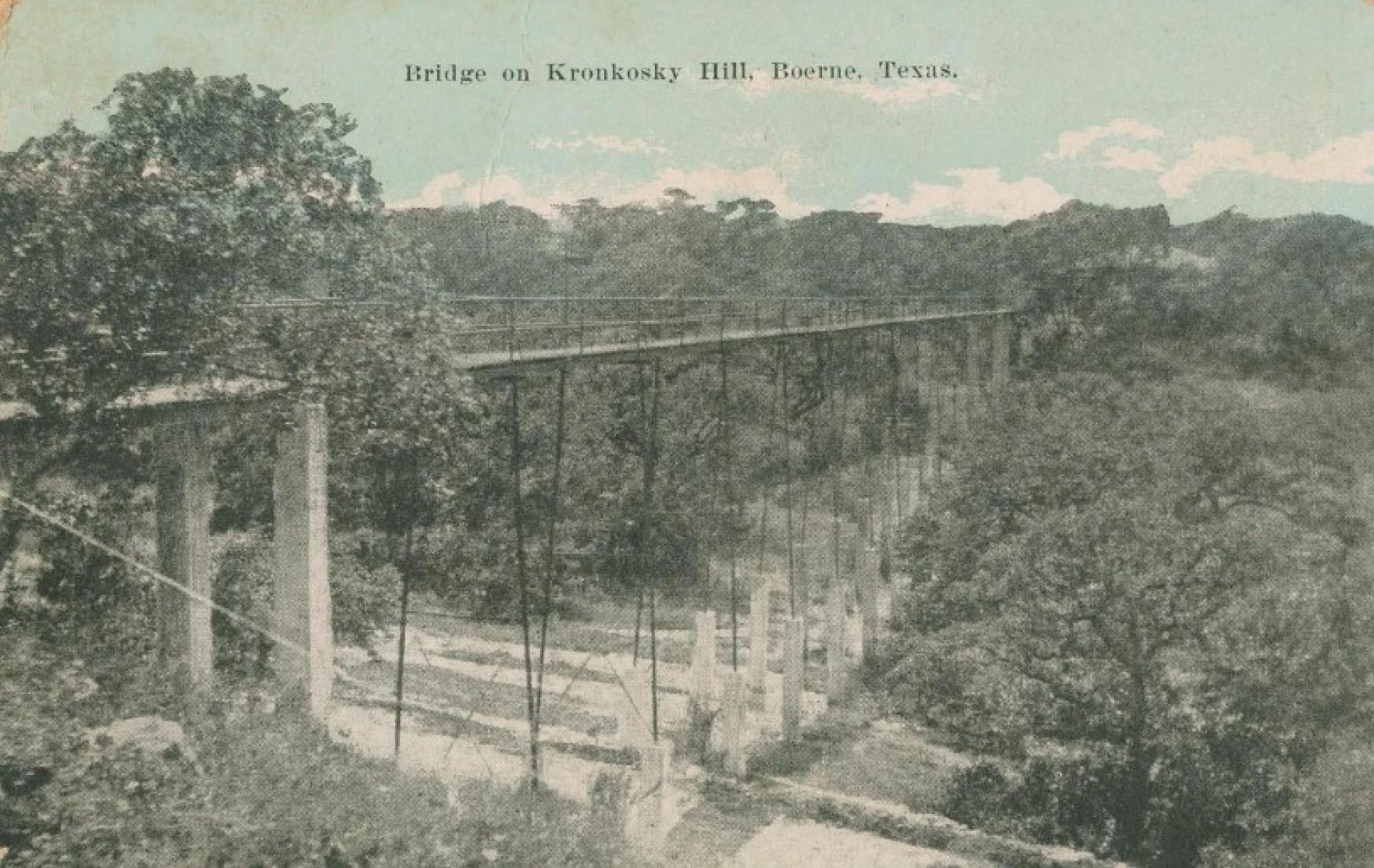

Each Texas town and city has stories to be told about its history, its architecture and its culture. San Antonio’s nearest Hill Country neighbor is Boerne, whose storied history is still quite alive, thanks in part to an eminent family.

If you’ve been there, it’s almost hard not to notice one building that looms over the Hill Country town — a distinctive 4-story tower on Boerne’s highest hill. Paul Barwick has spent the last 30 years working for the city.

“A beautiful piece of property that has a valley, a couple of hills on either side, has a fantastic view of downtown Boerne,” he said.