On Valentine’s Day 1930, Bonnie Parker wrote a letter to Clyde Barrow that began sealing the bond that would hold them together, come hell or high water, until they died in a hail-storm of bullets four years later.

Clyde had just been arrested and was sitting in jail in Dallas, where he might be sent off to Huntsville, at the age of 20.

Bonnie sent him a letter saying that somebody had sent her Valentine’s candy. In her coquettish way she declared: “I didn’t appreciate the old candy at all, and I thought about my darling in that mean old jail and started to bring the candy to you. Then I knew that you wouldn’t want the candy that that old fool brought to me.”

For Clyde, trapped in a cell with no release in sight, to have his crush reveal a suitor like that probably set Bonnie’s hook into him deep and tight.

But Clyde returned the favor when he got transferred to Waco to face seven criminal indictments and certain sentencing to years in Huntsville. He asked Bonnie to sneak a gun into the prison. Jeff Guinn, a biographer of Bonnie and Clyde, pointed this out succinctly: “He was asking her to risk everything for him. And that was so romantic.”

They say that Bonnie and Clyde fell in love at first sight and that the dysfunctional sparks flew right away. They shared complementary degeneracies that masqueraded as true love. He was the original bad boy, and she craved adventure. Think Sid and Nancy addicted to Browning Automatic Rifles in a Model-T Ford and violent robberies.

Somewhat ironically, though, Bonnie seemed to crave the thug life and life on the run with guns. She wrote poetry and love letters – and so did Clyde, to a lesser degree. Clyde, for instance, once wrote these words to Bonnie:

Dear Baby,

I just got your letter, and I sure am glad to get it because I’m awfully lonesome and

blue. … I’m just jealous of you and can’t help it. And why shouldn’t I be? If I was

as sweet to you as you are to me, you’d be jealous, too.

Bonnie liked traditional poetic forms, with rhyming stanzas. Here is a verse from her most famous poem, The Trail’s End, in which she seems to say they could be happy if the world would leave them alone. This is their struggle:

The road gets dimmer and dimmer

sometimes you can hardly see.

But it’s fight man to man

and do all you can,

for they know they can never be free.

The poem is famous mostly for its last line, which foreshadows their violent end.

Some day they’ll go down together

they’ll bury them side by side.

To few it’ll be grief,

to the law a relief

but it’s death for Bonnie and Clyde.

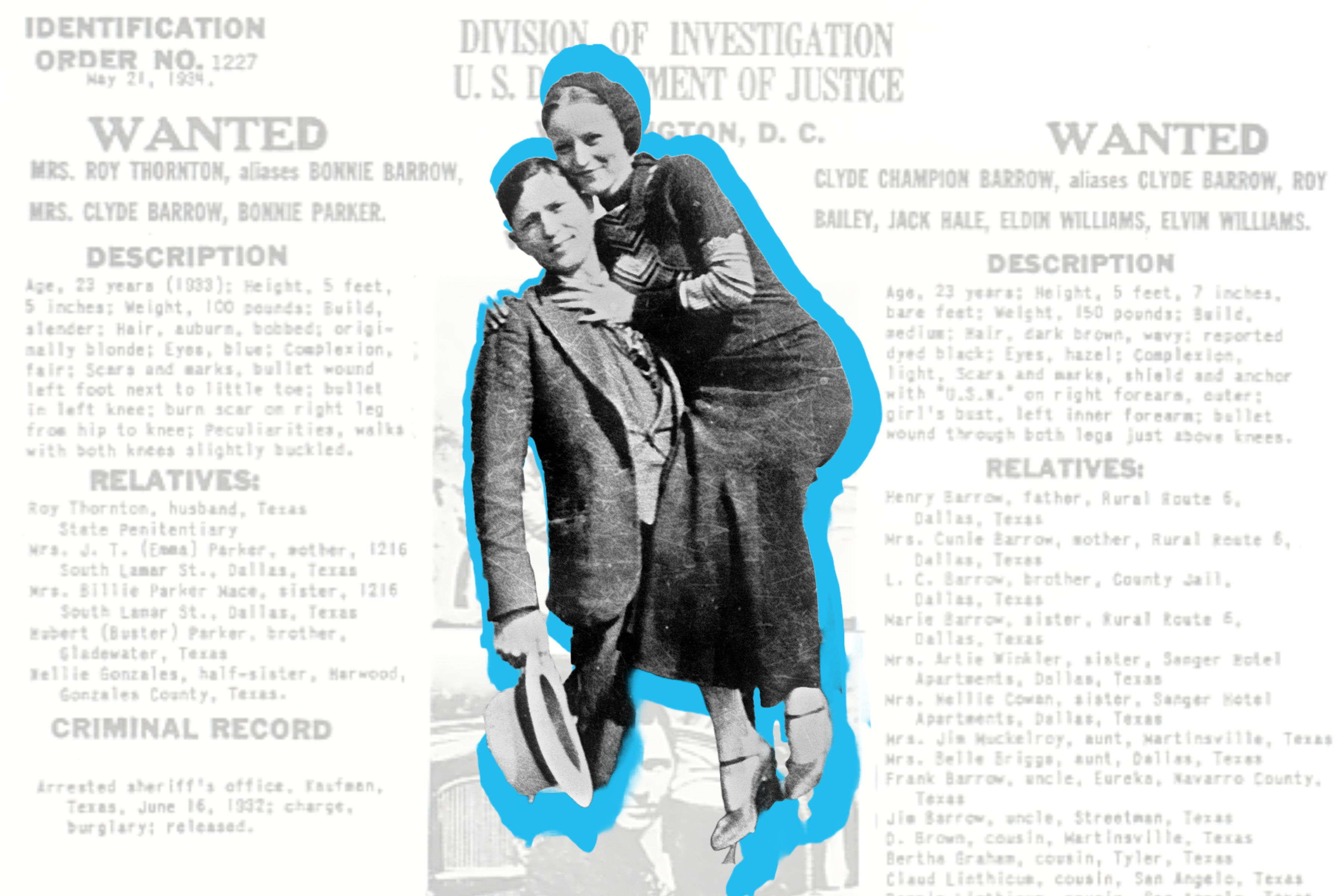

One highly unusual dimension of their love, and the element that has made them genuine icons as outlaw lovers, is that they took and posed for many photographs with their souped-up cars, guns and stylish clothes. They were Instagramming their street cred.

Their photos went viral in the 30’s. Newspapers printed them across the country, and their anti-hero branding gave them an undeserved but unrelenting Robin Hood image. So persistent was their self-made sympathetic image that Hollywood reinforced it with the Academy Award-winning film “Bonnie and Clyde” starring Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway.

It continues to this day. Right now, for Valentine’s if you’d like, you can even get his-and-her matching Bonnie and Clyde hoodies.

Besides Bonnie, Clyde had one other great love, and that was with the Ford V8. He was so impressed with it that he wrote a letter to Henry Ford himself declaring it the best car of all for his profession:

Dear Sir,

I have drove Fords exclusively when I could get away with one. For sustained speed and freedom from trouble the Ford has got every other car skinned, and even if my business hasen’t been strickly legal it don’t hurt enything to tell you what a fine car you got in the V8.

Yours truly Clyde Champion Barrow