This article originally appeared on Marfa Public Radio.

Mexico’s Comisión Federal de Electricidad, its federal electricity commission, has awarded a contract to a group of Texas companies to build two pipelines, including a 143 mile natural gas pipeline from the energy-rich Permian Basin of west Texas to the border with Mexico.

The line, known as the Trans Pecos Pipeline, would run through ranch land where some landowners vehemently oppose the project.

In Texas, pipeline builders can seize private land because many pipelines are classified as being in public good because they carry natural gas, crude oil or other commodities to customers who might otherwise not be served.

The pipeline operators are then designated as “common carriers,” meaning they carry commodities from at least two producers to customers who might otherwise not be serve.

A Texas company called Energy Transfer is leading the consortium selected to build the pipeline.

That a pipeline is even contemplated here is terrible news to ranchers such as Val Beard. She’s not only a rancher but also the former County Judge of Brewster County, Texas, a vast border county.

“It is not only illegal but profoundly discourteous. It’s just not done out here,” she said.

She was describing a recent day when she learned that a pipeline was planned here, a laregly unspoiled wilderness known for sprawling vistas covered by cobalt skies and starry nights.

She said she came across a stranger’s vehicle.

“We looked and we saw a brown truck and we stopped,” she recalled.

She says she approached the driver.

“And he told us quite unabashedly that he was surveying for the pipeline. We told him he had no permission to be there and would have to vacate the ranch.”

In an email, the company’s PR firm said Energy Transfer apologizes for the trespass, though Energy Transfer hasn’t given an apology directly to Beard.

The PR firm says a surveyor contracted by the pipeline company said he was sorry after Beard confronted him at the ranch.

With that designation comes the power of eminent domain. Now, hundreds of ranchers have received a form letter.

“I really bristled. The whole approach signalled bad faith,” said Beard of the letter that hundreds of area ranchers and landowners have received.

She described it as “an exceptionally vague letter from Energy Transfer.”

The letter asked for permission to enter private land without specifying exactly where, which rankles people in a region where property is measured in square miles.

Beard’s family has raised cattle in this border region for five generations.

But her opposition isn’t solely sentimental. It’s about money. She fears habitat her animals need might be compromised or that tourism to a pristine landscape, a significant economic driver in the area, might suffer.

Granado Communications is Energy Transfer’s PR firm in Dallas. An account coordinator there, Lisa Dillinger, wouldn’t address the perception held by some people that Energy Transfer has stumbled in its overtures to landowners.

“We sent out over 300 letters asking for survey permission all of which are vital to identifying the safest and most reliable route,” she said.

In Mexico, rancher Epidio Bonilla says he didn’t even get that. Mexico plans to build a pipeline that will link up with the proposed Texas line.

“Engineers from Mexico City showed up at my ranch,” he said in Spanish.

He said the engineers said they were contractors working for Mexico’s state owned oil and gas company, Pemex.

“They showed me where the pipeline would go. I told them,’not here.’”

But in Texas, bureaucrats and politicians in two hardscrabble border counties are revving up.

“You can’t drop 760 million dollars in a 150 mile corridor without all the businesses doing well,” said Brad Newton, Economic Development Director in Presidio, Texas.

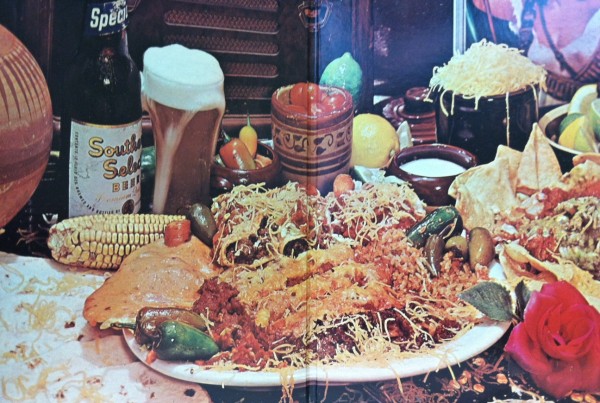

Presidio is hoping to reconfigure its economy as a border service center for the oil and gas industry, especially now that Mexico has signaled its intent to rescue its underperforming energy sector by opening its domestic energy market to foreign participation.

“You’re going to have people needing to eat, needing to sleep, they’re going to be buying stuff. You know, there’s pipelines everywhere,” said Newton.

Pipeline opponents are on mixed but evolving legal ground. In 2011and again last year, the Texas Supreme Court ruled against a pipeline company. But that case is under review in state court.

Texas has however toughened standards for companies seeking eminent domain.

Previously, they merely checked a box on a form that asked if they were common carriers, meaning carriers of other companies’ oil and gas.

Still, John Tracy at Texas Christian University’s Energy Institute cites a case where a family was only able to dealy the inevitable.

“The pipeline still went through. But they were compensated significantly more than the common carrier was willing to pay,” Tracy explained.

Another rancher, Greer Brunson, says he’s stopped previous attempts by other pipeline companies to access his land.

This is what Grunson says surveyors told him on one occasion.

“We can force it. And we’ll give you lot of money. ‘You’re not listening.’ The answer is no,'” he said replaying his reply.

In Mexico, rancher Epidio Bonilla doesn’t want compensation.

‘I wont lease my land for the pipeline. I’ll defend it,’ he said in Spanish.

So will rancher Val Beard.

“The question is, who is really going to benefit from this pipeline? And if our counterparts in Mexico are asking the same questions, might be that there’s some hope here,” she said.

The company’s planning three public meetings.

That was announced by 23rd District Congressional Representative Will Hurd, R-San Antonio.

In a statement dated April 7 2015, Hurd wrote;

“After talking with officials from the company yesterday afternoon and expressing my deep concerns over a lack of transparency, I am pleased to share that three open houses will be hosted by Energy Partners in the coming weeks.”