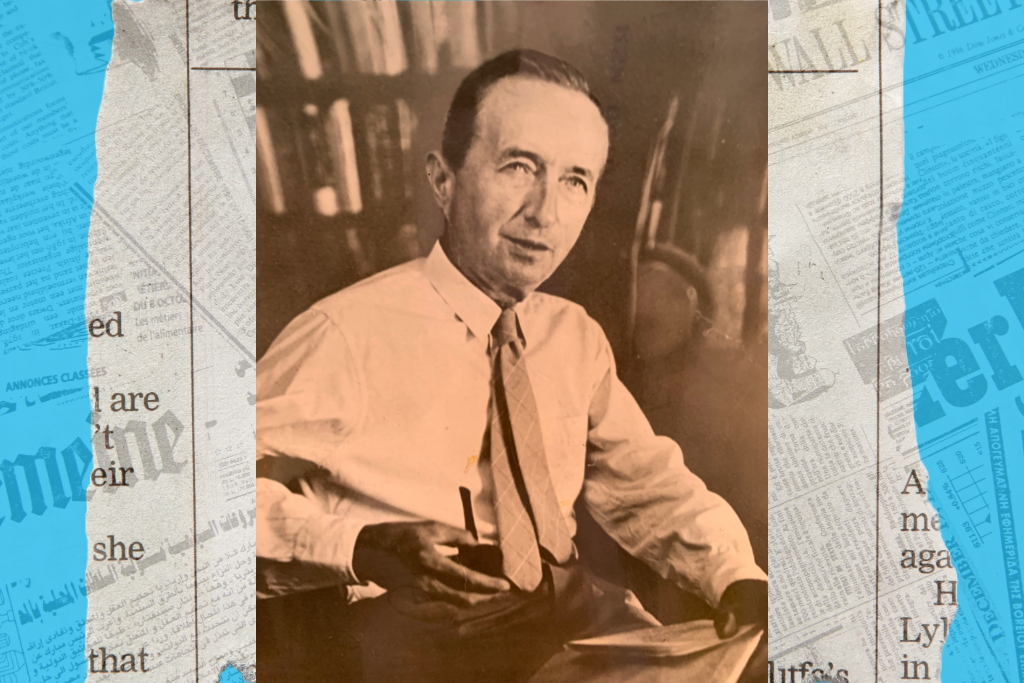

Texas has had more than its fair share of larger-than-life characters, which is why you’d be forgiven for missing Stanley Walker.

He was raised on a family farm 15 miles northeast of Lampasas. After earning a journalism degree from the University of Texas in 1918, he worked for local newspapers before moving to New York City.

Walker went on to become the city editor of the New York Herald Tribune and wrote a book called “City Editor” that chronicled rollicking tales of newsroom culture during the dawn of the tabloid age.

His stories inspired the next few generations of journalists, too, including Sean Corcoran, executive news director at the NPR station in Northern Colorado, KUNC. Corcoran spoke with Texas Standard about his motivation to dig into Walker’s history.

Listen to the interview above or read the transcript below. This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Texas Standard: What was it that interested you in Stanley Walker’s story? Are you from Texas, or do you have any Texas connections?

Sean Corcoran: I’m not from Texas. The first time I was in Texas was earlier [in 2023] when I went to Walker’s homestead.

I am from Massachusetts, and when I was about to go off to journalism school at about age 24, I found this book, “City Editor” in a bookstore, and it just grabbed me. Now, first of all, [Walker] hated journalism school. So that was kind of funny because I was about to head off to the journalism school, but it really had an impact on me, just this whole world he described in New York when he was there, as he was covering the rise of the mob and covering the starlets and prohibition, which began right after he arrived.

Now, why is it that Stanley Walker is not a better known name in Texas?

He’s the most famous Texas journalist you probably never heard of. But he was famous in his day, both in Texas, around the country, and particularly in New York. But that’s kind of faded away for the most part.

When I went to go visit his homestead, his family showed me an old newspaper clipping of a journalist who was doing just what I was doing, going to look for the cabin that he rehabilitated, where he wrote his books and his magazine articles. So he was a big deal for a long time, and now we’ve just kind of forgotten him. Editor of The New Yorker – I mean, just very, very prominent guy.

Tell us a little bit about the reporting style that he is known for. What distinguished him among his peers?

Well, first of all, with his peers, he was extremely influential and a real leader and really highly respected. Now, this was the tabloid age of New York. There were dozens of newspapers. He was in one of the most prominent ones, and he arrived and within just a few years he was essentially running it as city editor, and he helped kind of move the whole industry into a much more literary type of writing.

The kind of short crime stuff, he did that for several years, but then he really kind of came into his own with his writing, and there was a real movement kind of away from that to a much more, you know, kind of New Yorker-style writing that we saw after World War II. And so he was very prominent in that, and he just seemed to really help out his peers, get them connected.

And at The New Yorker, though he was only there for a year, he’s really credited with bringing in writers because he knew so many writers, and they ended up staying there for decades and decades and really building up that that staff and helping make The New Yorker what it became.

» GET MORE NEWS FROM AROUND THE STATE: Sign up for Texas Standard’s weekly newsletters

He made such a splash in the Big Apple. And yet he abandoned New York and returned to Texas to raise cattle and sheep. What was the story there?

It was a big farewell. I think he wrote about it in the Saturday Evening Post. And if you read it today, what he wrote when he was leaving, this farewell to New York, it would sound very familiar. He felt that the place had changed. He felt that it wasn’t what it was when he first arrived. And people often feel that way about a place that they have been.

But I also think that he didn’t want to just slip into obscurity. He really didn’t want to be some bore in the corner of a newsroom getting older and just telling stories about how it used to be.

And he also longed for Lampasas. He longed for Texas and the life that you live on a ranch. And he went back and chronicled it in his book “Home to Texas.” And the place was just an absolute mess. And that began the next chapter of his life, just resuscitating this pioneer cabin that he ended up living in, and this 300 acres of ranch land.