The COVID-19 lockdown era was, in some ways, defined by isolation but also by the power of community – particularly with the rise of racial justice protests after the 2020 police killing of George Floyd.

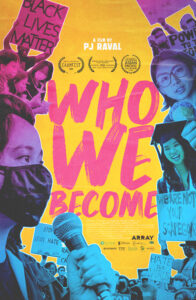

Austin-based filmmaker PJ Raval weaves in both themes and examines the most turbulent issues of the era through the self-documented stories of three young Filipinas in “Who We Become.”

Raval spoke with the Standard about why he made the film and what he hopes audiences will take away.

“Who We Become” is currently streaming on Netflix.

Texas Standard: I understand directing this film gave you some hope during a very trying time. Can you talk about that a bit?

Texas Standard: I understand directing this film gave you some hope during a very trying time. Can you talk about that a bit?

PJ Raval: I think we’re living in such turbulent, unprecedented times. There’s a lot of division and a lot of divisiveness. And I think that certainly is reflected also at home for some people.

And I think in this film, we see three individuals equally passionate about what they believe in and what they think. I’ve been calling it a little bit of a coming-of-age documentary because we really do witness them kind of coming into their own. And they’re not afraid to share this with their families, even though they know that their families may hold different opinions and different perspectives.

So, in a lot of ways, I’m hoping that it will inspire people to do the same.

Tell me about your three protagonists.

When we meet Lauren, she is returning home to Bedford, Texas to experience her college graduation over Zoom. So her story starts very early in the pandemic, when things were really emerging and things were very much locked down.

And then we go into Monica’s story where she tells her parents that she would like to attend a Black Lives Matter peaceful protest after the death of George Floyd. And they encourage her to stay at home instead and to not get involved. And, of course, Monica makes her own decisions, and that kind of sets her on a journey.

And then our third protagonist is Jenah Maravilla, who’s based in Houston, Texas. And Jenna had a long history of being a nurse and had recently quit to dedicate her life to activism and community organizing. And when, as you can imagine, the pandemic was occurring, she was really questioning her life choices and if she had made the right decisions. And we see her kind of, you know, going through what a lot of us did, which was self-reflecting upon where are we currently in this moment and where do we think we’re headed?

I know you’re also from a Filipino background, but I’m interested in why the perspective of Filipino women was especially important to you to highlight?

I think this idea of holding different points of view and different perspectives can sometimes be a really fracturing experience for families. But I do think, in Filipino culture specifically, there is this idea of, you know, love and respect for your parents and for the generation. And I think it’s through that concept of love we see these Filipino Americans figuring out a way to be vulnerable, to have these difficult conversations and still manage to navigate that space between them and the generations ahead of them.

Did you ever consider adding in some of your own experiences?

Every documentary I make is deeply personal on some level. And when I am watching the film myself and I see the different, you know, uncles and aunties and mothers and dads, I think very much of my own family. And I think for me, that’s why I was interested in also having three Filipino American women, because seeing them all together, we really understand the kind of common experiences.

Monica Silvero, far left, on a road trip with her family that is documented in the film “Who We Become.”

Directing, I would imagine, would be rather different at the height of the pandemic. How were you working with your leads to document their stories?

The unprecedented times kind of also opened the door for exploring new ways of storytelling.

So for this film, in particular, I really wanted to embrace this more collaborative storytelling process and really think about how this younger generation, or should I say younger than me generation, has really embraced different forms of media and storytelling, whether that be posting on social media or, you know, having a podcast or something. So I wanted to include this kind of everyday storytelling technique and really let the protagonists truly capture their own stories and choose what they’re going to share with us.

So a lot of the film is self-documented. A lot of the film comes from me having these very intimate and deep conversations with the three protagonists about what was going on in their life and how could they capture that. And, you know, just a little bit of what I think I would love to see in terms of what they’re capturing. And so it truly was a collaborative and really deeply satisfying artistic process.

I heard your crew was entirely Asian-American. What do you think that did or brought to the story?

I have to say, the film itself was edited by an amazing Filipino American woman named Katrina De Vera. The film was produced by Cecilia Mejia, who also comes from Filipino descent. You know, our executive producer, our co-producer, you know, you name it, it’s filled with Filipinos and Asian American women. And I think that’s not a coincidence.

All of these people, you know, these stories deeply resonate with them. There is something that really kind of binds our experiences together, especially as children of immigrants.

For a lot of people, I think 2020 seems so long ago in some ways. But the film’s release still resonates. What were you trying to communicate here?

Sadly, there has been a lot that’s changed and not changed, right? We’re coming up against an election soon. You know, there’s still the COVID, you know, the virus is still out there. And sadly, there will be a continuation of violence against communities of color despite the changing times.

And so these are things that even though the film is covering them starting in 2020, these things kind of remain. And I think by watching the film, I think what people will realize is what it takes to change these things truly are the community participating and binding together, right? And trying to figure out a way to have a sense of allyship and solidarity amongst each other and recognize that we’re all hopefully working towards the same good.

There’s an underlying theme in your film that’s best described in Tagalog. What is the word that I’m looking for there?

Yeah. So at the beginning of the film I share a definition of a word called “kapwa,” and that is a Tagalog word or, you know, the language from the Philippines, and it doesn’t fully translate into English. And what I have kind of described it as is it can maybe loosely translate to “togetherness” or “shared identity,” you know, “community.” There’s beautiful, poetic definitions, like “I am because you are.” You know, things like that.

And for me, when I think a lot of, you know, my experience here in the United States, when I think of the United States, I think of American exceptionalism, I think of individualism. And when I think of the Philippines, I do think of this concept of kapwa and community, you know, family, friends. And so for me, that became an influence and a guiding principle in making the film. And I think by watching these three stories together, you get that sense of kapwa. But you also maybe get that sense of kapwa and how it extends to the larger community.

And for those of us living, you know, in the diasporic communities, our families come from the Philippines – we’re maybe first or second generation living here in the United States. I think we’re realizing our experience parallels other communities of color, such as the Black community, such as the Latinx and Latine community. And I think what we’re realizing is we’re all working towards the same thing. So we hopefully have kapwa amongst each other.

If you found the reporting above valuable, please consider making a donation to support it here. Your gift helps pay for everything you find on texasstandard.org and KUT.org. Thanks for donating today.