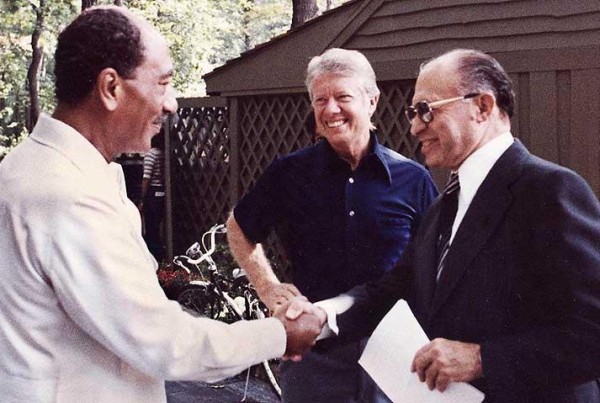

This week, civil rights leaders and politicians including President Barack Obama and three former presidents – Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush – gather at Austin’s LBJ Library and Museum to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act.

The occasion also has many Texans reflecting on their own experiences growing up in the Jim Crow-era south.

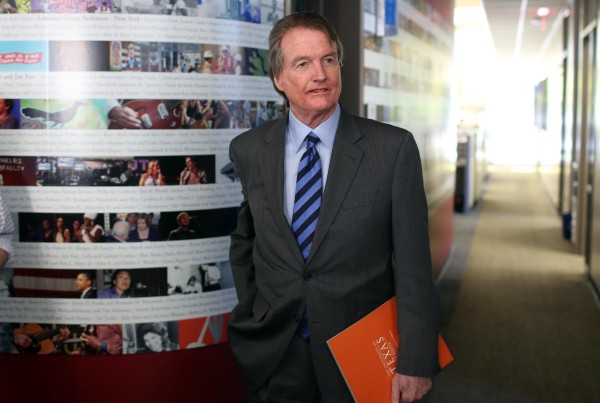

Travis County Judge Sam Biscoe said his exposure to the speeches of President John F. Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, and Dr. Martin Luther King influenced his activism.

Born in Tyler, Texas in 1946, Biscoe came of age surrounded by discrimination.

“[Tyler] was about as rigidly segregated as it could be. As I look back, the amazing thing is that that was life, and I was too young to question it,” he said. “When I was in high school, though, I did. At that time, the civil rights movement was underway in a way that attracted attention, so I was serious about the news, listening to the radio, reading the newspaper, and could hear the speeches by the Kennedys and Dr. Martin Luther King.”

It was during that time that Biscoe realized what he wanted to do.

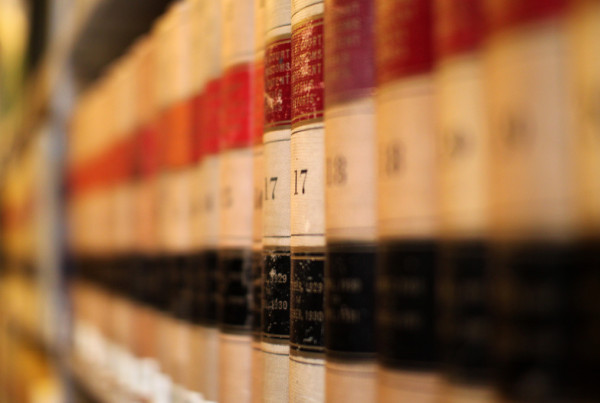

“During that time, ministers and lawyers were, in my view, having maximum impact. My mom had groomed me for the ministry, or teaching,” Biscoe said. “On my own, I decided that becoming a layer would be more meaningful, and in high school I decided that I wanted to become not only a lawyer, but a civil rights lawyer.”

Briscoe went on to study law at the University of Texas School of Law where he served as president of the Student Bar Association, and interning with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. He is set to retire this year after serving 25 years on the Travis County Commissioners Court.

Another civil rights activist, Ovide Duncantell, found other avenues for changing racially discriminatory laws.

Born in Natchitoches, Louisiana in 1936, Duncantell relocated to Houston in 1959 after leaving the United States Air Force. “The remnants of segregation were still in existence here,” he said. “However, I decided not to complain about these things; I decided to do something about it. I decided to run for public office.”

When Duncantell arrived at City Hall to file as a candidate for city council in 1971, the clerk turned him away for failing to meet two requirements. At that time, the City of Houston’s charter required that all candidates must own property within the city, and pay a filing fee. For Duncantell, it would have cost him $500.

“I thought something sounded highly unconstitutional about that, but she said that is the law,” Duncantell said. “So I went out, and got myself an attorney, and we went to federal court, and filed against the City of Houston. Later it was ruled in our favor … property ownership, as a qualification to be on the city council was unconstitutional”

“Also, [the judge] said you have to offer citizens alternate ways to get their name on the ballot. So we brought into the city of Houston, it had never been done before, that you could get your name on the ballot by petition.”

Duncatell was able to run for public office in later elections, but lost those races. In 1974, he founded the Black Heritage Society, where he continues his community action to this day.

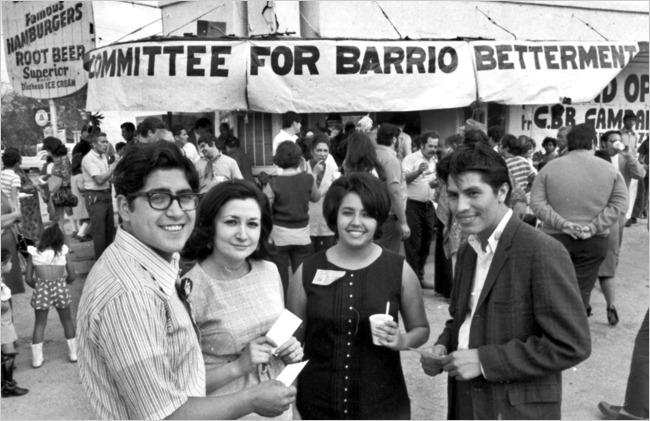

The civil rights movement also saw Mexican-Americans seeking political and social inclusion. Rosie Castro, born in 1947 in San Antonio, said she was struck by the poor educational system in place at that time. “One of the things that was predominant was that as Latinos, we had a very high dropout rate. At that point, when I’m in school, the dropout rate was at 80 percent, and the college going rate was at 4 percent.”

In high school, Castro and other students formed a youth organization that would give presentations around town. It was that experience where she first realized it was possible to speak out about the injustices she saw in her community.

She says that despite still having work to do – citing education and immigration reform as examples – the progress has been rewarding. “The changes have been great, we fought for changes through the political system, because there was not representation,” Castro said. “The promise of liberty and justice for all, I think is part of what keeps people all with their eye on that prize of working towards a day when all Americans are treated equally.”