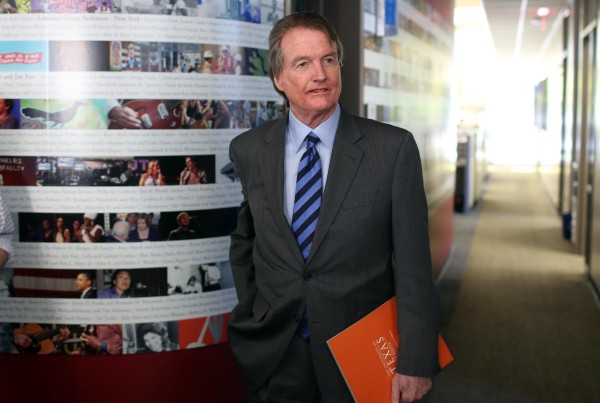

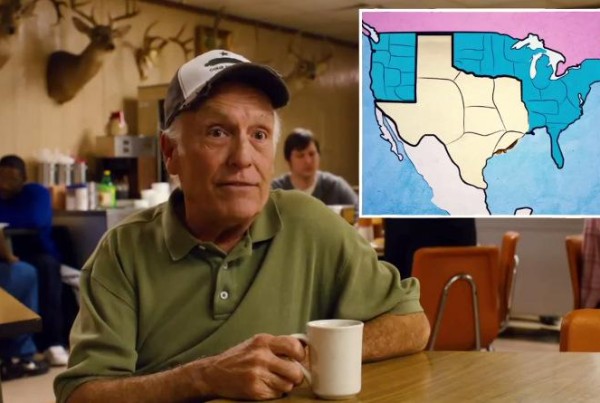

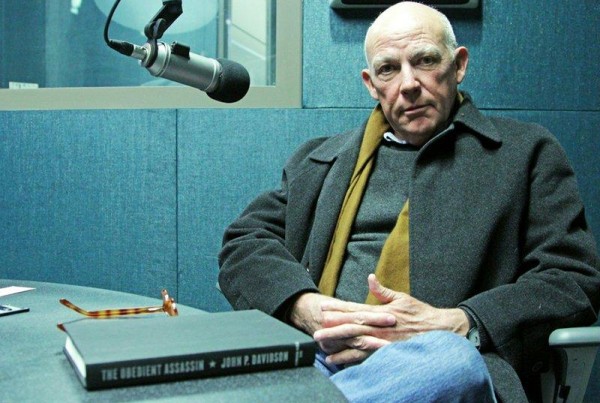

Chris Tomlinson spent most of his life comfortable that he knew who he was and where he came from. After all, a small part of Texas was named after his ancestors.Tomlinson Hill is a small town community in Falls County. It’s a place where generations of his family carved out a comfortable living from the land.

Before the Civil War, they also owned slaves. But Chris grew up believing what he’d been told: that the slaves his family owned were happy – so happy they took the family name and settled the land after they were free.

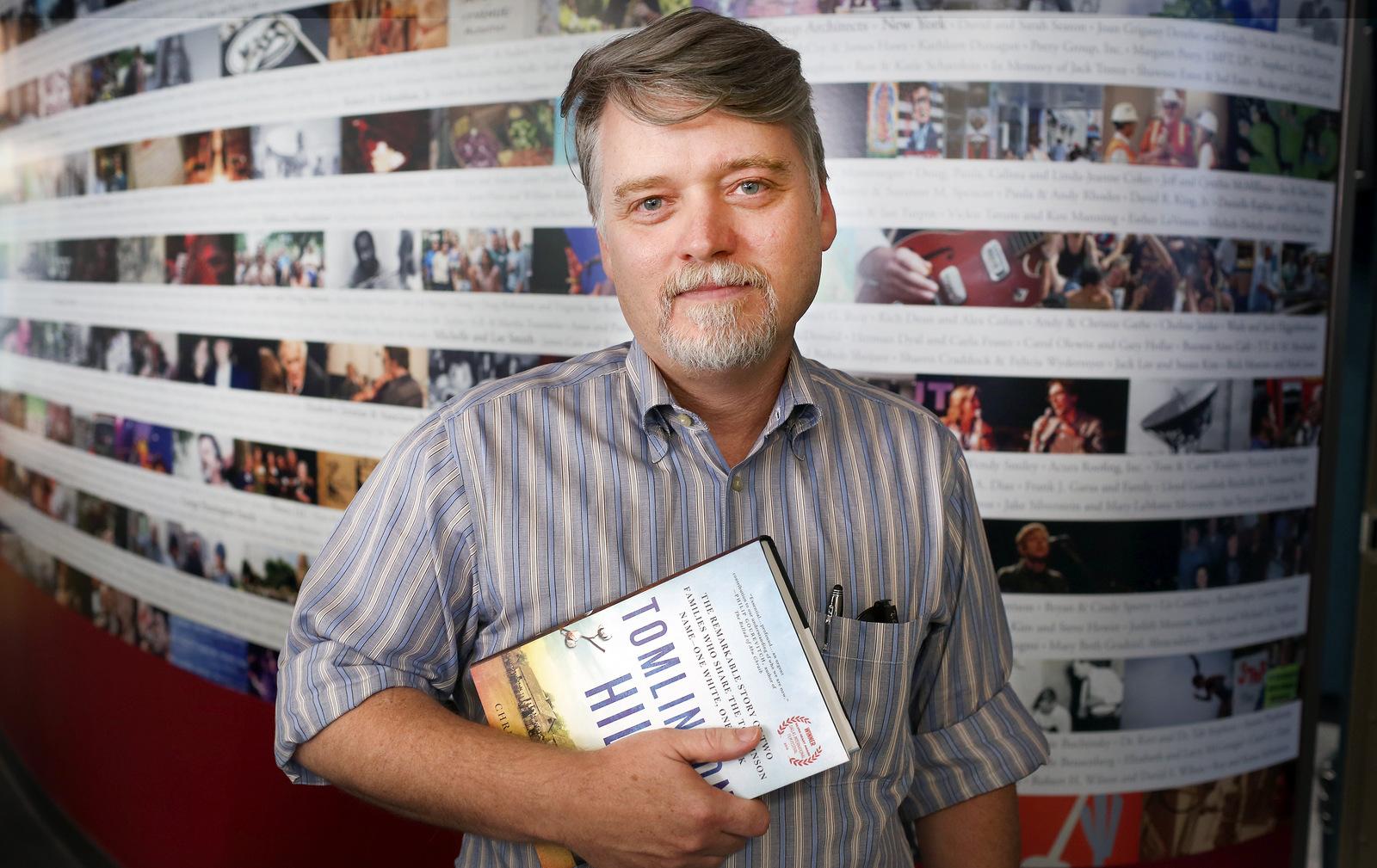

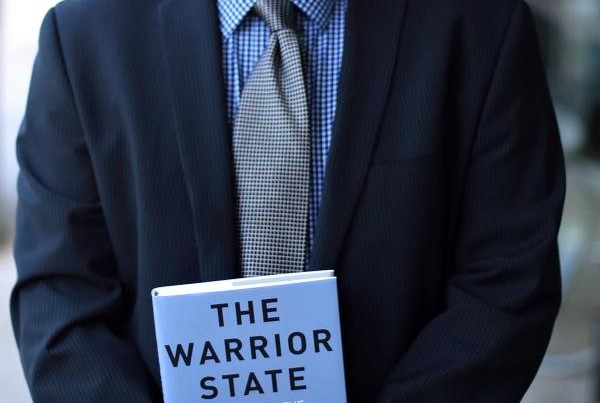

It was not until after he returned from 11 years in Africa as the Nairobi Bureau Chief for the Associated Press that Tomlinson decided to delve into his family history. What he learned not only changed his sense of family, it changed his sense of history as well. The result of his search is the book, “Tomlinson Hill.”

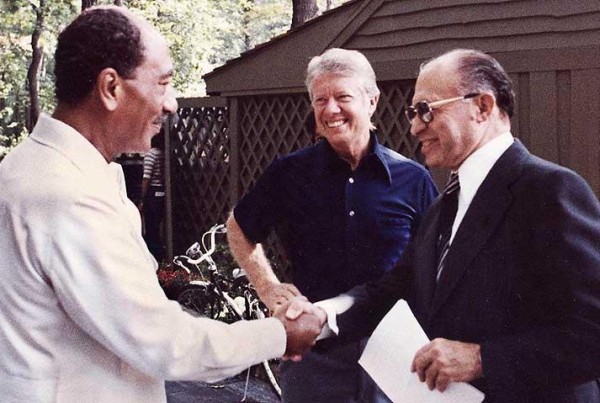

“I was privileged to witness the end of apartheid in South Africa, and I later covered post-genocidal Rwanda,” Tomlinson tells Texas Standard host David Brown. “And as I watched these nations struggle with the crimes of the past, the one thing I came to realize was that the only way to have true reconciliation was to have a shared, commonly accepted sense of the past – of the truth of what actually happened.”

The process of reconciliation that took place in South Africa, for example, enabled victims to confront the perpetrators of crimes. That process never took place in the United States. Tomlinson says when he was growing up, no one spoke about who perpetrated slavery or Jim Crow laws – they were just accepted as a fact of life.

“After having my grandfather talk about how glorious the family history was – even though we owned slaves and we maintained sharecroppers until the 1970’s, I realized I needed to do some digging and get to the bottom of what my family’s role was in that part of American history,” Tomlinson says. “My grandfather was quick to point out that our family owned slaves, and they loved us so much they took Tomlinson as their last name. And then my father would wince and say … maybe that’s not the real reason the black Tomlinsons took our name.”

While Tomlinson’s parents were liberal and uncomfortable with the family’s past, his grandparents were more conservative, and hewed more closely to family tradition.

“I first thought about this when my grandfather was telling me these stories in 1972,” he says, “when I was a little kid and living in Dallas during the beginning of busing and the desegregation of Dallas schools and the busing riots of Boston, This was also the same year that a teacher played a tape of Martin Luther King’s speech in class. And when I heard the line, ‘I have a dream that the sons of slaves and the sons of slaveholders will come together on the red hills of Georgia at the table of brotherhood.’ I realized I am the son of slaveholders, and there are sons of slaves out there with my family name. From that point on I wanted to meet those people.”

But that thought faded into the background for decades. “And it was only after I was an adult that I began to realize that the family history that I’d been taught was horribly one-sided, probably factually inaccurate and needed to be examined,” Tomlinson says.

He began his search with published histories – the ones written by whites. He then went and looked at oral histories of freed slaves. Then, he narrowed those histories down to Central Texas. From there, he went talking to every Africa American over age of 80 that he could find in Falls County. He collected their oral histories and their family tales. “For this book I did over 200 oral histories,” Tomlinson says, “all of which are now part of the Baylor Institute for Oral History. Some of them are available on the [book’s companion] website where we let people speak for themselves.”

Tomlinson spoke with members of the black Tomlinson family, all of whom are direct descendants of a Tomlinson Hill slave named George who was born in Africa in 1820. He heard from “the most famous Tomlinson of all, a running back named LaDanian Tomlinson who played for the San Diego Chargers [and] agreed to an interview and … agreed to write the foreward for the book.”

What was interesting, Tomlinson says, is how similarly their fathers approached the Tomlinson history. “Their father was like mine. It was a history he didn’t want to share with them. He didn’t want to share how he had spent his youth as a sharecropper picking cotton. He didn’t want to talk about the family slave past. He wanted them to focus on the future. So in many ways, there is this post-civil rights generation of blacks and whites – and I would say of all Americans – who aren’t learning their history. And that was also a motivation for digging into it and writing this book.”

You can hear Tomlinson’s reasons for delving into history that many didn’t want uncovered by clicking on the link.

Tomlinson will speak at Austin’s BookPeople on July 23 at 7 pm.